The Problem with PE

The case for private equity is not a hard one to make. Its returns were consistently ranked among the highest compared with all other asset classes.[1]

The challenge is implementation. Put plainly, PE funds are difficult for individual investors to access. There are a number of reasons for this.

Firstly, most PE funds target institutional investors who deal with far larger sums of capital. The minimum investment required by most funds is, therefore, often a seven-figure sum (e.g. $5 million).

Furthermore, to avoid concentrating risk in a single fund, most PE investors spread their capital across 10 or even 20 different funds for maximum diversification. Even assuming a modest investment of $2.5 million per fund, this equates to $25-50 million of total committed capital.

Not only this, but the terms of PE investments typically lock up investor capital for the duration of the fund’s life (10-12 years).

It is therefore understandable that private equity remains out of reach for non-institutional investors, who cannot afford this level and duration of capital commitment.

How Evergreen Funds Help

This limited access is a genuine problem. 99% of companies are privately held, and so there are many more opportunities in the private markets than in the public markets. What has been lacking until recently is a way to gather and deploy the capital of thousands of individual investors to make the most of the opportunities.

This is where evergreen funds enter the picture. As the name suggests, such funds do not have a fixed lifecycle like typical “drawdown” funds (raise capital, deploy capital, return capital).

Investors are able to add and withdraw funds with greater freedom (i.e., without the decade-long lock-up period). Perhaps more importantly, evergreen funds can offer far lower entry thresholds, in some cases as low as $25,000, well within the reach of the typical affluent investor.

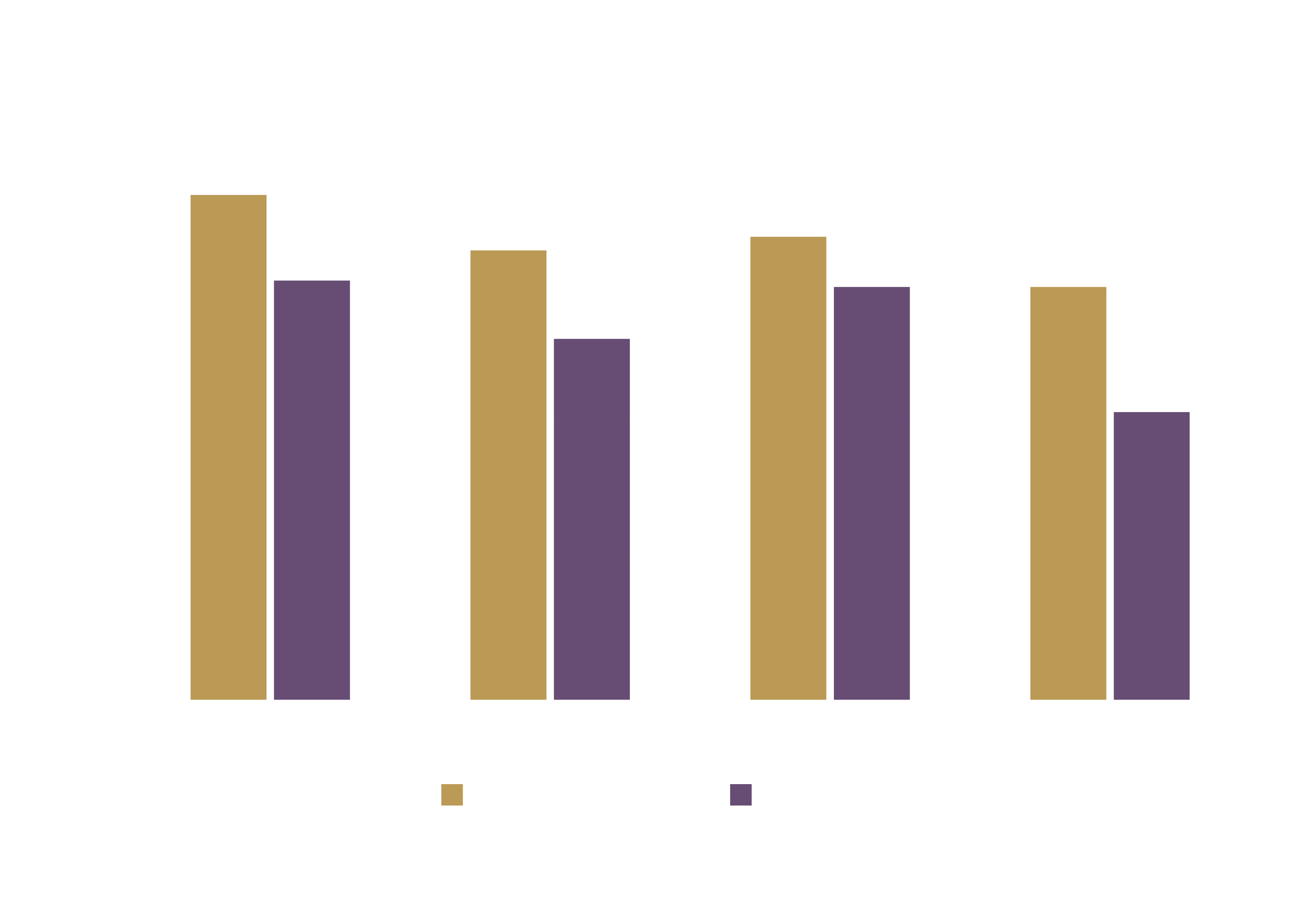

Evergreen funds that act as ‘multi-managers’ also provide access to top-tier traditional PE funds that might otherwise be out of reach to individuals. This is important, as performance between different funds varies considerably, and securing access to a top-quartile PE fund could deliver as much as 14% extra annual return in comparison to a bottom-quartile fund.[2]

Too Good To Be True?

At this point, it would be right to ask if this is not all too good to be true, surely, this higher liquidity must come at a cost? And surely the high minimums at traditional firms are in place for a reason?

Both observations are correct up to a point.

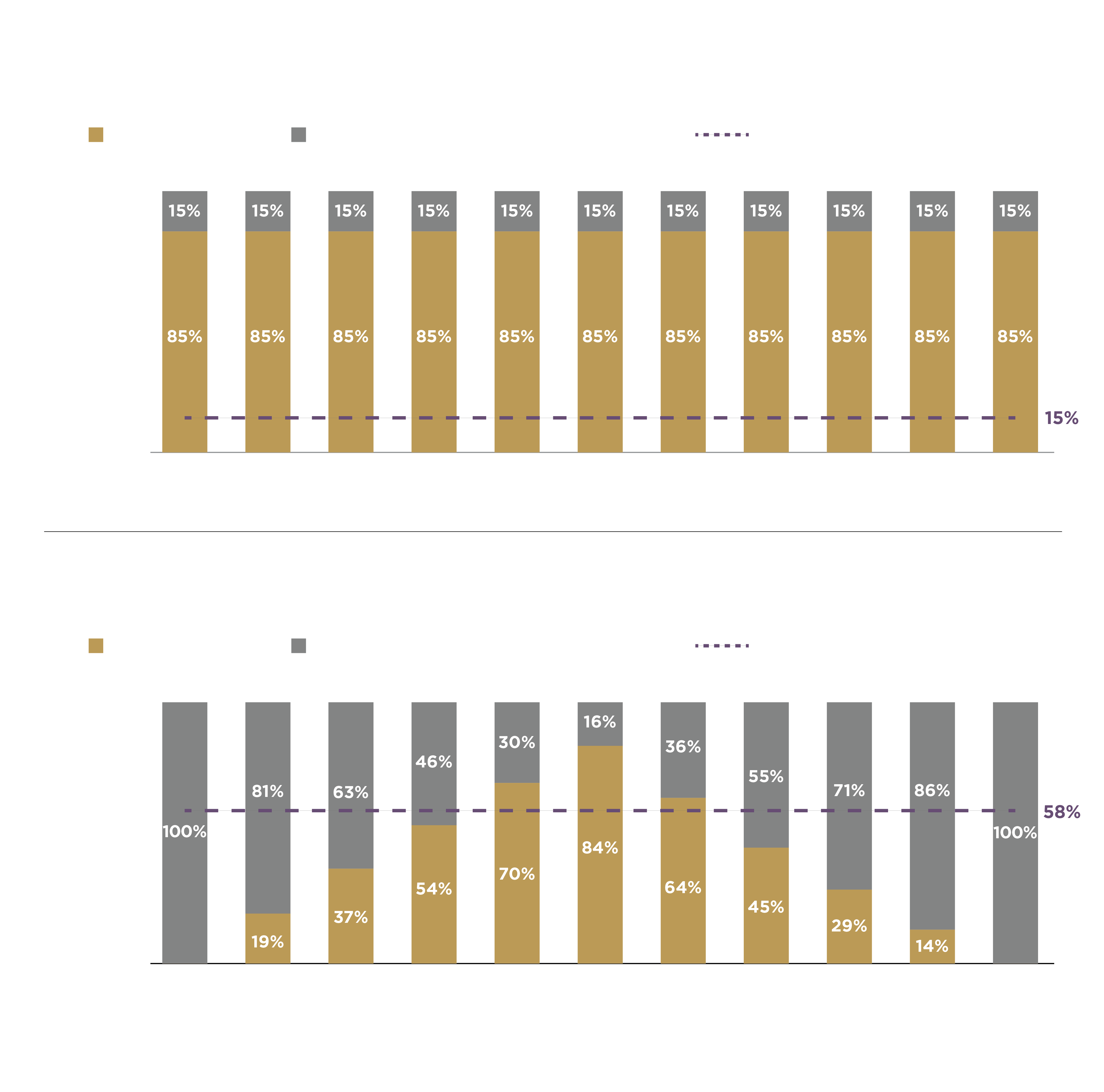

It is true that there is a cost to the higher liquidity. In evergreen funds, part of the invested capital is kept in a so-called ‘liquidity sleeve’, to ensure that funds are available for investors who wish to withdraw. This liquid portion of the funds is lower-earning, which does have an impact on returns.

It is also true that evergreen funds are more regulated and have unique operational complexities involved in running them (particularly ensuring that inflows and outflows do not disrupt the workings of the fund), and this complexity naturally translates into a higher cost for the investor.

However, the above is offset by two important factors.

One, the flexibility of the evergreen model allows diversification by sector, manager, and geography, meaning that the overall risk of the investment is lower.

Second, investor capital is put to work from day one. This contrasts with the ‘drawdown’ model, where most of the capital remains essentially idle for much of the fund’s life. The contrast is shown in the chart below, the blue portion denoting ‘actively deployed capital’ - in other words, genuine “private equity”.

Source: Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.

Source: Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.

The slow start inherent in traditional drawdown PE is behind the so-called ‘J-curve’ phenomenon, where returns can be low or even negative in the initial years of a fund’s life. This is avoided in the evergreen model.

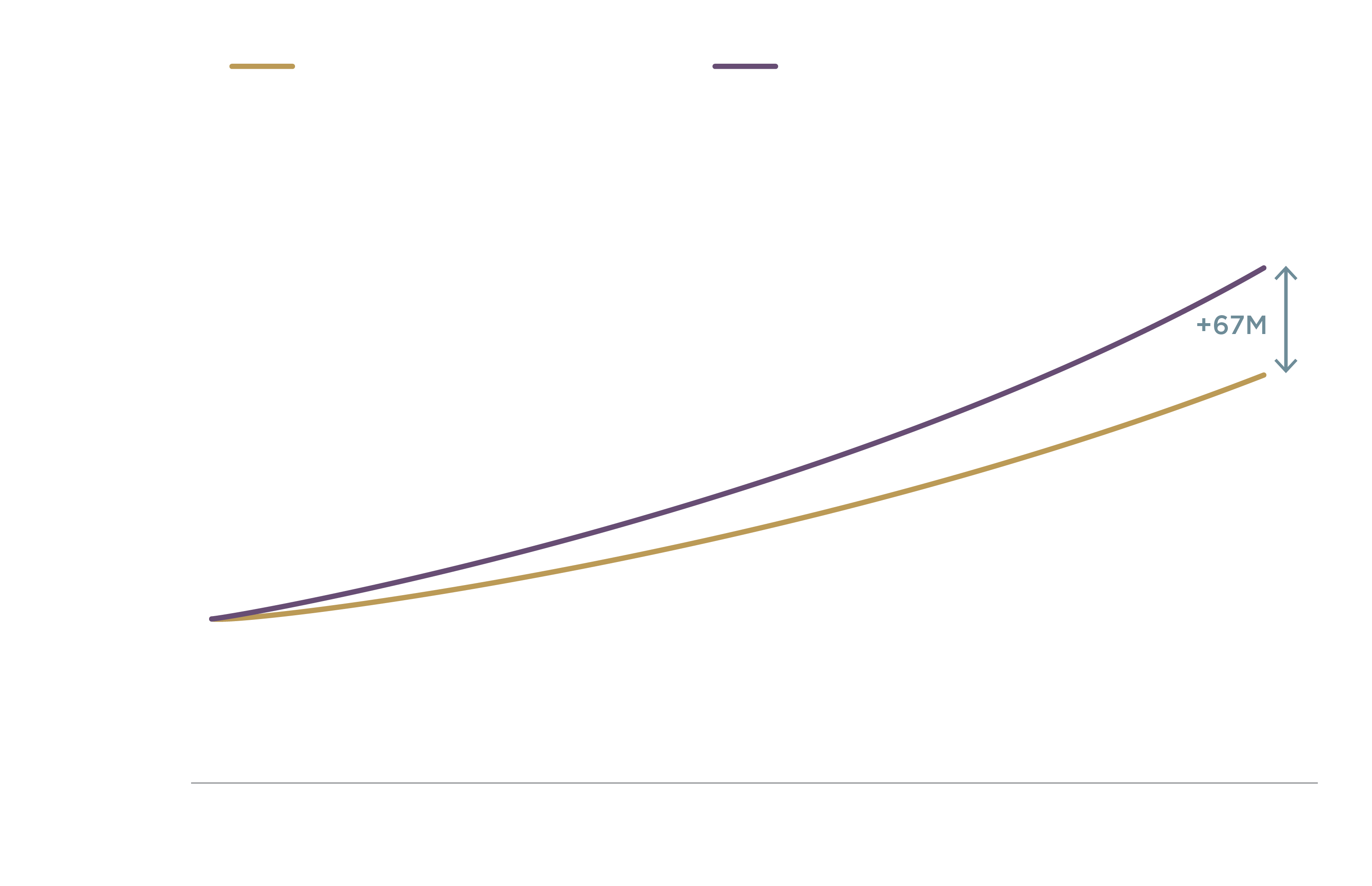

An analysis by KKR[3] shows that an evergreen PE strategy can equal or exceed that of a traditional, drawdown-based strategy.

In addition to potentially higher returns, the benefit for the individual investor is, as noted, one of initial access and ongoing liquidity, neither of which the typical model can offer.

Conclusion

This article has been a very brief precis of the case for evergreen funds. They are not a miracle “cure-all” solution, but do represent something genuinely new and useful, insofar as they broaden the universe of PE for both investors and firms looking to raise capital.

Data from Preqin shows that the number of global evergreen funds doubled to more than 500 in the years between 2018 and 2023, accounting for more than $350 billion of capital.[4] The fact that even institutional investors are interested in it as a solution underscores its legitimacy, not only as an access-widener, but as a smart approach to gaining private markets exposure.

We believe it is a space worth keeping an eye on in the future.

[2] Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co.